The AI Hype: $600B question or $4.6T+ opportunity?

I respond to skeptics, who seem to be missing the forest for the trees.

As summer draws to a close, a familiar debate has reignited with renewed intensity. Are we witnessing the dawn of a new technological era? Or are we caught in yet another tech bubble?

At the heart of this debate lies what David Cahn at Sequoia calls the "$600B question": the revenue gap that must be filled annually to justify current AI investment levels. This figure, derived from NVIDIA's projected data center run-rate revenue for Q4 2024, captures both the enormous faith being placed in AI's potential and the challenges it faces in living up to those lofty expectations.

Wall Street's initial AI enthusiasm has cooled. Financial analysts are concerned that huge upfront investments in AI may never show actual returns. The Wall Street Journal seems to have a weekly slot reserved for articles questioning AI's business value, with "AI” and “bubble" predictably featuring in headlines. It's beginning to feel less like journalism and more like an SEO strategy.

Adding to the uncertainty is the fact that software companies are having a brutal few years. While the Nasdaq is up 14.7% in the past three years, software companies (as tracked by the BVP Cloud Index) are down 47.5% in that same period.

This month, I want to take a step back, survey this debate, and zoom out to the bigger picture: how generative AI is driving a fundamental shift in the way software creates value, moving us from SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) to what the investing team here at Foundation Capital is calling “Service-as-Software.”

The two-sided nature of technological revolutions

To understand our current AI moment, it's helpful to recall Amara's Law: We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate it in the long run. The dual nature of technological progress explains much of the tension in the current AI debate and highlights why it's so challenging to separate the genuine potential of an emerging technology from the inflated expectations surrounding it.

On one side, the flood of money pouring into AI is staggering. In just the first half of 2024, tech giants funneled a whopping $106B into AI development. Looking ahead, projections suggest we could see up to $1T invested in AI infrastructure over the next five years, a sum that rivals the GDP of all but the world's largest economies. This tidal wave of investment briefly propelled NVIDIA to become the world's most valuable company in June.

The private sector is following suit with equal fervor. According to Pitchbook, investors deployed 41% of their capital, or $38.6B, into U.S.-based AI startups in H1 of this year. This flood of cash has led to some eyebrow-raising valuations, often for startups with little to no revenue. Take Cognition, a coding-agent startup founded in November 2023. In March, it launched an impressive demo that went viral on Twitter. One month later, it closed a funding round valuing it at $2B, all without a publicly released product.

(Source)

Tech incumbents are also going all-in on AI. Sundar Pichai summed up Google’s stance on a recent earnings call: “When we go through a curve like this, the risk of under-investing is dramatically greater than the risk of over-investing.” Mark Zuckerberg echoed this sentiment, saying he’d “much rather over-invest and play for that outcome than try to save money and develop more slowly.” He continued: “I think there’s a meaningful chance that a lot of companies are overbuilding now, but on the flip side, all of the companies investing are making a rational decision. Because the downside of being behind is that you’re out of position for the most important technology for the next 10-15 years.”

Despite the massive investments, turning AI into a profitable business remains an unsolved puzzle. Many of the buzziest first-wave generative AI startups have folded into big tech. Inflection, Adept, and Character were effectively acqui-hired by Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, respectively. And even the tech giants are grappling with the challenge of turning AI breakthroughs into profitable, scalable products. AI products have technical limitations, regulatory uncertainty, and a stickiness problem. Users will often try generative AI applications a few times, marvel at the technology, and then move on.

Adding to the challenge are the poorer economics of AI-powered services. Unlike traditional software, where marginal costs approach zero as you scale, AI services have substantial ongoing costs that grow with usage. A recent analysis found that computing costs account for 22% of AI startups’ expenses: more than double what non-AI software companies pay. This threatens to erode the cushy 60-80% gross margins of traditional SaaS products. It’s also sparking debates about whether the era of seat-based pricing is coming to an end, giving way to more outcome-oriented models: paying for actual work done versus marginal productivity gains.

Generative AI may well be the most capital-intensive technology Silicon Valley has yet seen. OpenAI is reportedly losing $5B a year. Sam Altman upped the ante with a casual remark that he'd be willing to spend ten times that amount annually. The line between visionary investments and reckless spending seems increasingly blurred.

This disconnect between short-term hype and (as yet unrealized) long-term impact is fueling skepticism and cries of "bubble" from observers. Yet it follows a pattern we've seen in every modern technology cycle. Right now, we're somewhere between the "inflated expectations" and "disillusionment" phases of generative AI. If history is any guide, this doesn't mean generative AI is overhyped in the long term—quite the opposite.

The case for optimism

Here's where the optimist in me pushes back. Every technological revolution has its Pets.com, but it also has its Amazons, Googles, and Salesforces. As for bystanders ogling over AI capex, every major technology shift demands massive upfront investment. Think of the billions sunk into laying fiber optic cables during the dot-com boom, or the massive costs of building out cellular networks. These bets looked risky, even foolish, at the time, but they laid the foundation for the digital, cloud-based world we now take for granted.

Yes, generative AI is expensive today. But the technology's cost equation will change, as it always has.

A recent Goldman Sachs report gives a helpful example: In 1997, a top-of-the-line Sun Microsystems server cost $64,000. Within three years, you could replicate its capabilities for 1/50th of the cost using off-the-shelf parts and open-source software. The scaling this enabled led directly to the rise of cloud computing, which unlocked hundreds of billions in value through SaaS applications.

We are already seeing similar trends in AI inference where the cost of 1M tokens has dropped from $180 to 75 cents in 18 months: a 240x decrease.

(Source)

Another key point many AI skeptics are missing is how fundamentally generative AI is changing the way software creates value. We're witnessing a shift from Software-as-a-Service to what we at Foundation call "Service-as-Software." AI no longer acts as a tool, automating part of a job. AI automates the whole job, becoming the service provider itself. It won’t simply give you a CRM platform like Salesforce: it will manage your customer relationships start to finish. Instead of offering email marketing templates, it will design and run entire marketing campaigns.

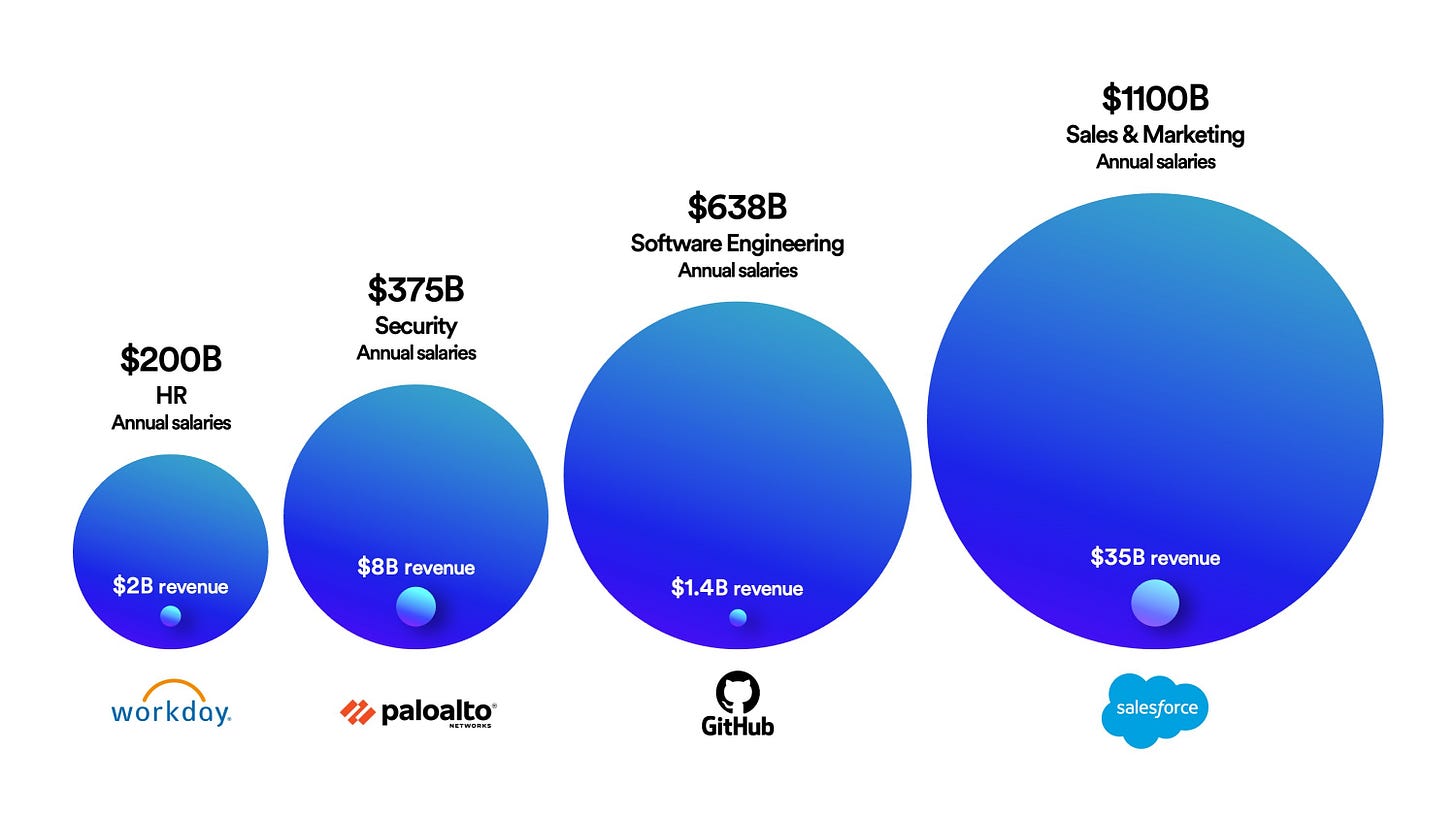

The shift explains why the potential market for generative AI is so vast. We're no longer confined to the existing software market; we're looking at software, salaries of jobs globally in a variety of functions ($2.3T in sales and marketing, software engineering, security, and HR; see chart below), plus the amount spent on outsourced services and salaries—both IT services and business process services ($2.3T per Gartner) as the new frontier for AI disruption. This is a $4.6T opportunity.

Despite the market's ups and downs, I believe generative AI's true potential is being dramatically underestimated.

Where I land

So, are we in a bubble, or on the cusp of an AI-fueled revolution?

First, to be clear: The hype surrounding AI is real, and it's intense. There's a palpable risk of overvaluation and misplaced investment. But here's the thing: That hype, as overblown as it sometimes seems, serves a purpose, attracting talent, capital, and attention to the field that’s necessary to drive innovation.

While David Cahn and other skeptics may fixate on short-term fluctuations (is the ROI of AI a $200B question? or $600B?), they're missing the forest for the trees. AI isn't just another tech bubble; it's a fundamental shift in how work gets done. Goldman Sachs senior economist Joseph Briggs estimates that generative AI will boost U.S. productivity by 9% and GDP growth by 6.1%, just in the next decade. The investment bank also identified some 300M full-time positions that will likely be automated within ten years, meaning our $4.6T tally above could actually be low.

It’s easy to forget how long it takes for new tech to gain widespread adoption. Consider the personal computer. The first PCs hit the market in the mid-1970s, but they didn't become household staples until the late 1990s. In 1984, a mere 8% of U.S. households had a computer. By 2000, that number had grown to 51%. Today? It's 95%.

AI is on a similar trajectory, but with one crucial difference: it's moving much, much faster. The capabilities of AI systems aren't growing in a straight line; they're exploding. Humans are notoriously bad at thinking in exponentials. As LLMs scale, they demonstrate new, emergent capabilities. Breakthroughs on the horizon in areas like model efficiency and hardware innovation promise to further accelerate progress.

So where does that leave us? It's prudent to approach the current AI hype with a healthy dose of skepticism. We should question the grandiose claims and try to separate the hype from the reality. But it would be a big mistake to dismiss AI as a bubble. The question isn't whether AI will change our economy—that ship has already sailed. The real questions are: How profound will that change be, and how quickly will it arrive?

Personally, I believe that today’s uncertainty will give rise to the next "magnificent seven": a new wave of AI-native companies that leverage the increasingly de minimis cost of intelligence to achieve $100B+ (or perhaps trillion dollar) market caps.

I liked this article and your term "Service as Software." I think with AI agents this is true and I also think the tables are turning a little on the traditional startup that is built by developers. I think, now, with the concept of AI agents, those with domain expertise and process expertise are the people you want to back creating a startup. Especially since coding can be done using generative AI.